You know the way the future used to be? I mean, that brilliantly utopic version of the future from The Jetsons, and Tomorrowland at Disney World, and even the crisp clean lawns of the old black and white movie The Day the Earth Stood Still, meadows untouched by so much as the thought of a dog encountering a tree, much less a fire hydrant?

The future was so bucolic, so nice. It was supposed to be. Even the darker side wasn’t so bad. There were Twilight Zone episodes where the monsters from space weren’t really monsters at all (they were ourselves), other episodes where the only villains we had to fear were viruses, or pandemics, or ideas, not exploding RV trucks or neighbors with human kitchens in their basement or our own government.

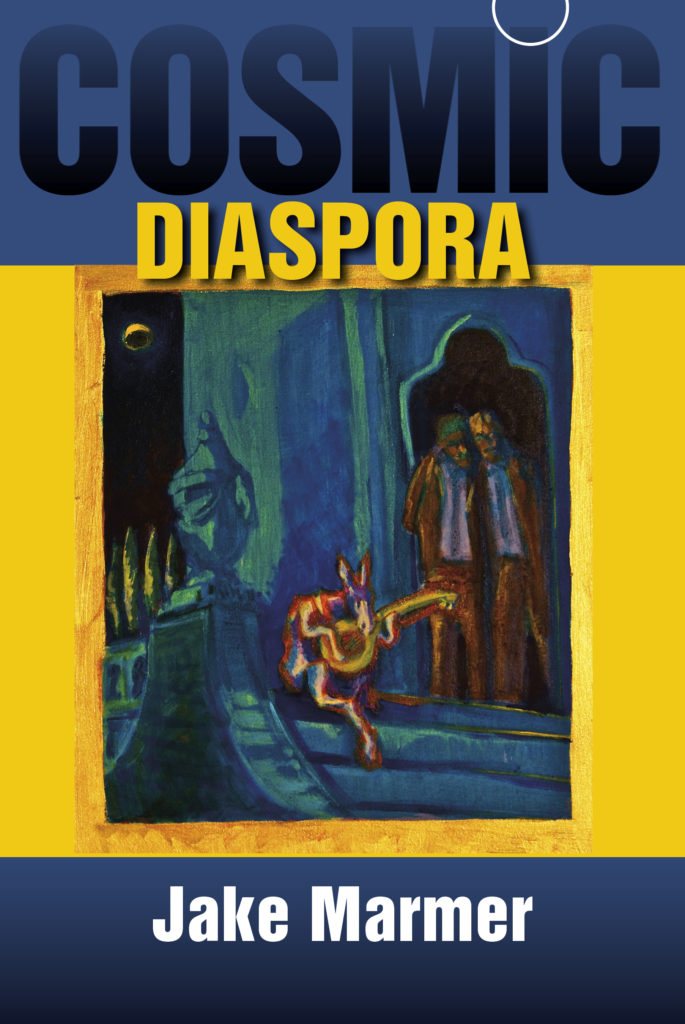

Jake Marmer’s new collection of poems, Cosmic Diaspora, hails from this pleasantly unpleasant tradition. (There’s also a companion album, Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire, made by the Cosmic Diaspora Trio, a jazz group that Marmer fronts.) The book opens with a quote from Sun Ra, the Philadelphia jazz musician and futurist:

the scientists discovered at last that

there are black holes in space

I wrote that some time ago

the earth

is one of those holes

Marmer’s poetry, which we’ve told you about before, embraces the beauty and the horror. Jake is Russian, which makes him say all sorts of brilliant and funny things about how the world is done for and we’re all going to die. He’s also a father, and in the quiet hearts of some of these poems, we find him wondering at the existential delight of love:

What I miss about my world the most?

There were these purple rocks you could talk to

and feel heard.

…

What I do down here, in your world devoid

of purple rocks? Talk to my beer. Don’t feel heard for shit

but I like the taste. And I think purple rocks,

if I were to taste them, would be similar

Throughout the book are sprinkled QR codes that lead to secret videos and audio tracks of poems (“Bar Stool Aliens,” the purple rock poem, is here), and it’s a nice companion to the book. In addition to a bit of emergent storytelling, it also feels thematically appropriate: each of these elements of the book — words, disembodied voice, video — are a different way of presenting and digesting each poem, and each feels incomplete, but when put them all together and your mind can sort of trace out a silhouette of the complete thing.

Arthur C. Clarke said that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. Society spent the past two hundred or so years setting up a war between science and religion, when really they’re both trying to do the same thing: explain the ineffable, and establish a set of rules or guidelines for our understanding of and engagement with it. In “No Eyes (after Zohar 2:94b-95a, 1:15a),” Marmer writes:

in the beginning, a burning mirror to erase

the dream of semblance, created

the dream of the missing alef,

which became the breath

of Elo-kim

(Italics his; the break in the name mine.) I have so many questions. If it’s the beginning, how is there a burning mirror? Was it just created now? If there’s nothing else in the world, what can it reflect? And how can it erase things? There were moments in the book where I swore I’d walked in halfway through an unspeakable occult ritual in an old horror movie — a cloaked figure with horns intones a weird and ghastly and yet somehow familiar phrase, the virgin on the table gasps, an aura around the table begins to glow — and the words flow in, almost of their own accord.

But it’s not actually like that at all. Marmer really is writing about the familiar here. In one piece he calls himself an “unlibrarian,” describing himself as devouring discarded news articles and erased literature; throughout he wrestles with passages from Zohar, the predetermination of gematriya, and, fascinatingly, with his own work: “I heard a voice say: Jake! / don’t let the poem’s critical mass / hijack its vanishing point.”

What do poems do? These days, we want the things we read to be easily explainable, to tell a straightforward story. On the other hand, there’s a lot of modern poetry, the kind with a bunch of words stuck to a page with no seeming reason (“concrete starfish blacknblue jill,” you know the type). Marmer’s poems are neither, but instead exist in the valley in the middle, understandable but not simple; with a story, but one that he’s reading even as he tells it; and that he’s a part of, but so are we, all characters in a story of our own creation, the science fiction of the moment that’s about to happen.