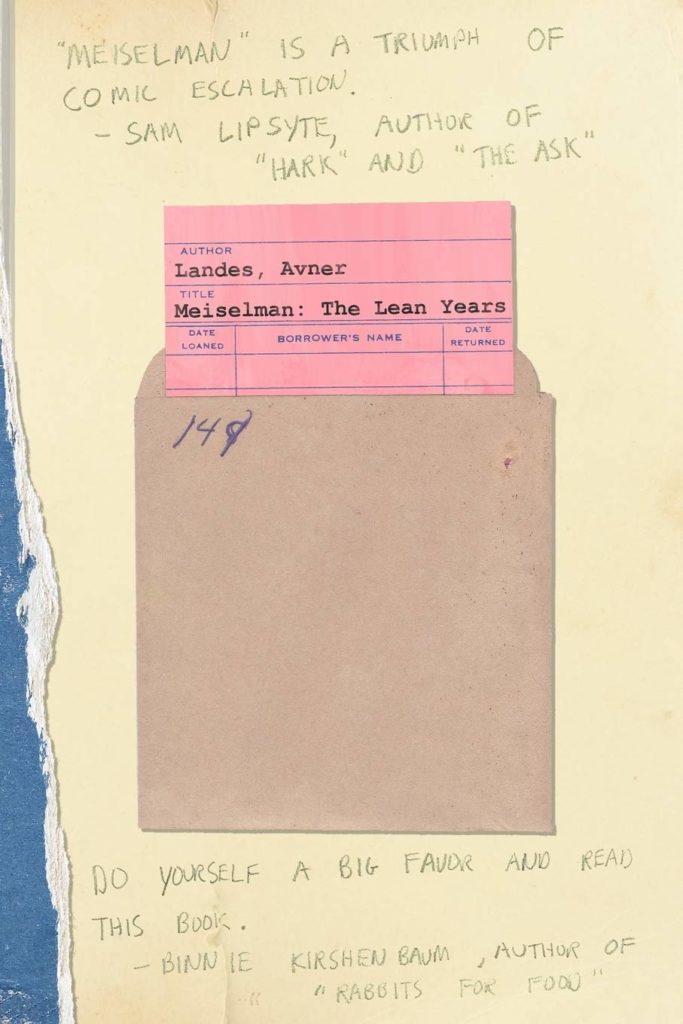

Avner Landes’ richly told debut novel Meiselman: the Lean Years is an irreverent Bildungsroman centered around the neurotic life of Meiselman. After enduring a series of workplace humiliations at the public library where he coordinates special programs, Chicago bred, Orthodox practicing husband/son/librarian determines not to remain a push over. “Where had thirty-six years of letting up and standing down gotten him?” So begins a week-long romp through a series of ill-conceived power moves with everyone in his path, from his elderly neighbor to his newly observant wife, culminating in a much hyped literary event with famous author and former classmate, Izzy Shenkenberg. With his “mop of curls tightly clustered like a cauliflower floret,” Meiselman is dogged in his pursuit of the elusive win. “Winning has to be practiced, worked into every action, every utterance.” What could possibly go wrong?

Landes grew up in Skokie, Illinois. After a decade in Israel, he moved to New York City for his MFA at Columbia University, returning to Israel in 2016. By day, he works as a ghostwriter and editor with over a dozen titles not to his credit, from memoirs to self-help books, and how-to financial guides. He lives outside of Tel Aviv with his wife and children.

This summer we met through Julie Zuckerman’s online reading series Literary Modiin, when I was a guest, and stayed connected through the Internet, as people do. (It all came full circle when Landes appeared on the line-up for this month’s event.) We chatted on erev Purim, a few weeks before Meiselman’s publication.

You’re in Israel, about to launch your American debut. During a pandemic. I have to ask — How are you doing? I can only think how Meiselman would have fared in Covid.

It feels insensitive to talk about one’s own Covid experience when so many people are suffering. Nevertheless, I’m happy to speculate about how Meiselman would’ve fared during this period. Social interactions must exhaust Meiselman since he is someone who calculates every word and gesture for the effect they will have on the person across from him. Yet, he also has a need to feel humiliated, to constantly feel that he is the victim. That’s quite hard to do when you’re stuck at home. But poor Deena. How would his wife have handled being stuck with him? Luckily, she’s an essential worker.

His is already such an insular world, the pervasive claustrophobia rendered with such acute authority.

I don’t know if it’s the claustrophobia of a religious world as much as just the claustrophobia of living that is undoing Meiselman. Meiselman is not alone in experiencing his day-to-day life as claustrophobic, by which I mean he finds himself locked into distressing patterns or situations. Claustrophobia, however, can be a good thing. It’s a feeling, a signal that we need to search for paths away from these fixed patterns. Meiselman, unfortunately, knows so little about himself—his desires, for starters—that he can’t begin to articulate how his life might look different. Religion and rigid models, like that of masculinity, for example—are particularly oppressive and add to the claustrophobia in that they scare people off from entertaining those alternative choices that might lessen the claustrophobia.

As someone who grew up straddling the religious and the secular world, I have always been both drawn to and enraged by tradition. Like, whenever I got into trouble in public school, my dad would threaten, “That’s it, she’s going to day school!” For a long time, it was something I railed against. What is your relationship to Judaism?

I identify with the Modern Orthodox community. I keep kosher, and any writing I do on Shabbat is in my head. I’d say that my observance is more of a cultural attachment than a religious one. The question of G-d doesn’t inform my day-to-day. Sure, I’m curious, but I don’t lose sleep over it. Answering this question has me nervous about people reading too deeply into my religious affiliation. I like to think that I have some unique religious perspective, that I’m a rare breed in the Modern Orthodox community, but doesn’t everyone like to believe that their religious outlook is anomalous and complicated but, at the same time, well-considered and well-crafted? In reality, we’re all just struggling to let go of our parents’ hands and figure out what works for us.

In my book, the novelist Shenkenberg has abandoned the Orthodox lifestyle, and at his literary event the crowd is mostly Orthodox Jews that love him because of this rejection. His liberation thrills them. Why do we love the abandoners? Because the person’s determination inspires and reminds us that where we start off isn’t where we have to end up.

Shenkenberg, of course, feels zero remorse or obligation to uphold a sanitized view of religion. As his doppelgänger, did you ever question your choice to pull back the curtain of this closed world?

Many of the writers I work with [as a ghost writer] express concern, at some point, that they will hurt a loved one. I remind them that in the moment they are writing their story nobody is reading their work. Save your worrying for when someone will actually read it. (At this point, I tell them never to share their writing with family members. Does a doctor show her work to her husband or parents?) I’ve been able to take my own advice, and, when writing this book, I didn’t have voices warning me off. But the time to start worrying has arrived!

One of my biggest life struggles is caring what other people think of me. I can’t stand confrontation of any sort. For a variety of reasons, I’ve been able to get past it with my writing. Perhaps I never thought people would actually read it. I don’t believe in the idea that writers should have an audience in mind. It’s not our job as writers to have people like us based on what we’ve written. My parents are very supportive. Support is a double-edged sword. Support sometimes can feel like the other person is taking ownership of your thing, but the alternative, people not caring, is much worse.

Roth said “literature is not a moral beauty contest.” Speaking of Roth: Mickey Sabbath, Bellow’s Herzog, Bruce Jay Friedman’s Stern: Meiselman seems to be following in a line of idiosyncratic, wholly flawed and irresistible heroes. How consciously did you conceive of him within this legacy?

Unfortunately, I learned all of the wrong lessons from Roth, Bellow, and Malamud. As a beginning writer it thrilled me to see American writers writing about Jews and how they live. But I mistook this element as the crux of their message and spent many miserable years writing about Jews, as opposed to writing about people who happened to be Jewish.

Authors like Grace Paley and Stanley Elkin and books like Stephen Dixon’s Frog and Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater showed me a different way. Before them I didn’t appreciate how language creates characters or that I wanted to be the kind of writer that put an emphasis on delighting the reader at each moment and having faith that it would all add up to something. Putting the character, in other words, before the situation or the “message.” I didn’t feel I had the license to just write whatever interested me, to write without a plan, to let one scene tumble into the next one, something more consistent with how our lives actually unfold. Bruce Jay Friedman’s Stern is the book that helped me understand what I was doing with Meiselman, especially on a structural level.

I’m more aware of the writing that pushes me. I can remember how I felt the first time I read Nell Zink, or Alissa Nutting’s Tampa, or how I feel when I read Joy Williams, who I’ve gotten into lately and rather late in the game. Influences to me mean those writers that unlock those small things that are keeping you back. It’s almost undetectable.

I recently read a friend and former student’s newsletter on her novel process in which she wrote: “Obsessions can fuel our creativity, but in order for them to work (read: communicate ideas to other people) in fiction, I think it’s useful to figure out why we are obsessed. Underneath the obsession is usually an emotion or a question, and other people have probably felt the same emotion or had the same question, which means these can be used to open up the story to readers — to invite them in.” What are your narrative obsessions?

One narrative obsession is following how the mind moves. I have no real interest in writing realist fiction, or making sure that the thoughts of characters cleanly track with the plot. This may sound curious to some since I think my fiction does read as somewhat realist. But I think it’s a fine line, and I think straight realist fiction is less interested in seeing the absurd underbelly of the mind because it needs to keep its focus on the situation or scene. This connects to an earlier answer to the style of fiction I was writing before Meiselman. I see my style as stream of consciousness, and my obsession is trying to locate what’s holding all of these ideas together. The question that animates this book, and probably most of my fiction, is how does one break destructive patterns in one’s life. I’m also interested in trauma, particularly how we interpret the past. Many books are interested in presenting trauma as something static and use these fixed interpretations to connect the dots to the present. The big reveal that explains all. This book explores how our understanding of trauma changes as we discover more about ourselves and others—or as we sink deeper into our delusions—and how new understandings can hopefully help us break free from demoralizing patterns.

One of my favorite, most disturbing scenes of the book is when Meiselman brings his wife’s underwear to the rabbi for inspection while they are trying to conceive. I mean, I ROARED. But I was also deeply troubled by the act — and the innate misogyny of such a practice. Talk to me about Meiselman and the women in his life. How he relates to, and fails to relate, and why.

Meiselman, who only sees and appreciates people for how they impact his own standing in the world, objectifies everyone, meaning he, especially, sexualizes women. Why he is afraid of seeing women as something other than players in his sexual fantasies is one of the questions driving the plot, and it’s raised in an early scene when he won’t have sex with his wife because it’s too spontaneous and not at the time when they usually have sex. Sex, for Meiselman, is an obligation, a challenge he has to overcome, or as he thinks, “…he does enjoy the act, just not the anticipation.” Traditional ideas of masculinity and the duty to be fruitful and multiply have ruined sex with his wife. Without giving too much away, that moment with the underwear is a turning point for Meiselman. He’s suddenly the victim of the oppressive system and he doesn’t like it. Slowly he starts to understand that his fantasies don’t say anything real about anyone else and that the women in his life live fuller lives than him—low bar—and that they are all smarter and more accomplished than him. In the rabbi’s office, he begins to see that the fantasies and sexualization of these women reflect only who he is.

Victor LaValle calls narrative voice “personality,” consisting of everything we bring to the table. Meiselman is a novel of enormous voice. It’s interesting because you make a living as a ghostwriter. As someone who is constantly throwing one’s voice to fit another person’s sensibility, how did it feel to fully embody your own? (Also: in what ways has ghost writing helped or hindered your own work?) Roth’s The Ghostwriter is a contender for my favorite Roth novel.

When LaValle says “personality”—I went and read his brilliant answer, so thanks for sharing—he means viewpoint, the way the author engages the world. This is the one element of writing that can’t be taught. People, I’ve learned from my work as a ghostwriter, have little sense of what makes their lives interesting, and helping people figure that out is the challenge for teachers. You go through pages and it’s usually, “boring, boring, boring, ah, this shit’s weird and disturbing, let’s focus on that.” Which is the same way I approach my own work.

Meiselman is also an arrogant prick, at times. He thinks of himself as decent and considerate, when he’s actually indecent and only considers himself. But he knows that his arrogance is just a pathetic attempt to prop himself up. He’s a man barely keeping it together and is too scared to find out what he’ll discover once the façade crumbles. This was a “personality” type that was easy for me to embody.

As an Israeli and American, how does identity inform your sensibility?

I’ve always struggled with this identity question and being able to say that you try not to think about it comes from a place of tremendous privilege.

In New York, I felt much more conflicted about my various identities—Israeli, Jewish, Jewish orthodox. I felt like I had to choose a tribe and the group I picked was always at odds with who I was as a person at that time. In NY I felt like it was difficult for me to take a holistic approach to my identity. I’d be shutting my various identities on and off depending on the current company I was keeping. Kippa on, kippa off, baseball hat on.I’ll get the salad. I’ll just get a drink.

Since moving back to Israel, the ambivalence isn’t nearly as pronounced, partly because I think there are differences between being a Jew in America and being one in Israel. In America, Jews have to make major decisions about their religion—what shul they’re going to attend, where they’re going to send their kids to school. These decisions make statements about the person’s religious outlook. They box the person, to a certain degree. I see now that not having those decisions in my life has definitely lessened my angst when it comes to religion. Sure, there are other issues, or decisions, but I can go long stretches without thinking about the practical implications of how I practice my Judaism. I don’t know if I had that when I lived in NY. The discomfort was constant.

Your writing is so deeply rooted in place.

Some people have asked me about place, and I admit I’m pretty unaware of how I use place. What I do know is that it’s tough for me to write about places I’ve recently lived because it creates an obligation for accuracy. I need the distance to know that I can bastardize the place. I never want to feel obligated to make it an accurate depiction. Also, with this distance of time, your memory ends up fixating on certain facets, at the expense of a complete picture, and that’s a good thing.

If these are the “lean years,” what’s next for Meiselman? What’s next for you?

I think Meiselman is dead and buried but never say never. Maybe the money will be right for a sequel. I kid, but there’s always that fantasy playing. The pandemic sidetracked me from my new novel, which is set in Chicago, New York, and Israel. There are too many people in our apartment! I mean family members. So I’ve been writing short fiction. It’s hard as hell. I’m failing, which is making it a fun challenge. I have to bounce. Megillah time.

Chag Sameach!