When I get to the garden, I am paying no attention to the time, too focused on the sweet child’s small hand in mine. He tugs at my arm toward a couple chatting by the give-and-take bookshelf; he insists on greeting them, “Shalom!”

They stand up abruptly and freeze in place. I realize then, with a split-second’s delay, that that eerie, tinny-blare that sounds like time freezing, like colors fading, like that old familiar haunting shriek incongruous with the tenor of the sun’s warmth on my red hair, is whirring away above us. The sound transcends us, it happens at ten a.m sharp, would have happened at this time wherever we were. The siren does not care. It pays no mind to my priorities (getting the toddler out of his apartment so his parents can work and rest, keeping track of said toddler’s whereabouts and urination schedule, etc); it drones on at its designated time and lasts for its allotted slot. The siren begins without warning, amplifying gradually so that it feels as if it has crept up on us, a houseguest arriving unannounced, who cannot be banished. It will fade in its time.

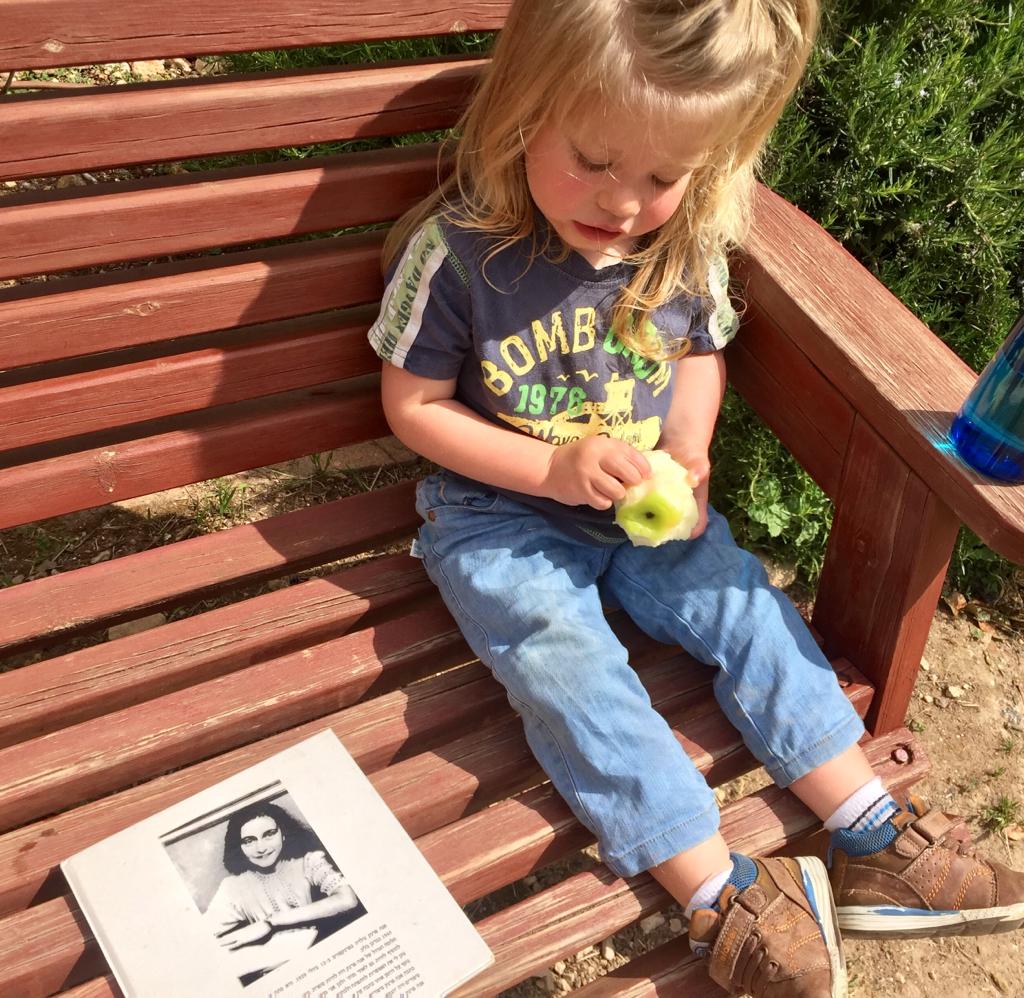

I scoop up the child who grasps his green apple with both hands, taking tiny, messy bites. He sinks into my arms and continues devouring the fruit in serenity. I hug him close to me, rest my forehead on his for a half-moment until he jerks his way aside to watch a stray cat’s wanderings. He remains oblivious to the siren, and to my sentiments.

Here I am, in the springtime in Jerusalem, where I live safely and in abundance, holding a beautiful Jewish child whose parents nurture him with kindness and embody values of peace. Here I am, holding space for all the brokenness that paved the way to this moment, to this vision of a dream. I am flooded with quasi-poetics, reflections on the pain and triumph of our people, reveries on the tender wonder of life itself. My heart opens, and there are no words, and it is just right, and also too much, and the siren winds down from a wail into a whining echo, dispersing just as it came.

We find our usual bench, the one to which the boy has gravitated for the past week or so, the one that Thomas, the friendly neighborhood cat, is usually hiding underneath. The speckled cat has been conspicuously absent lately and the child inquires, before his attention leaps to the volunteers repainting the nearby benches. They beam upon seeing his smile, his cheeks already rosy from seven minutes in the sun. He notices the book I’ve pulled out from my bag; we’ve read it before and it’s one he adores, but selfishly, this selection was in service of my own emotional longings, an effort to fulfill the day’s requisite mourning. By the way, did you know that Anne Frank wrote children’s stories?

It is Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Memorial Day, and I am sitting in a neighborhood garden in Jerusalem, reading Anne Frank’s The Wise Old Dwarf to a babbling toddler.

We read about Dora, the privileged, gleeful girl without a care in the world. She flits about her cushy life, irritated whenever Pheldron, the town’s grouchy beggar, appears in her midst. Pheldron has no tolerance for Dora’s carefree ways, her laughter grating to his gloomy sensibilities. Neither can imagine experiences beyond their own narrow lenses, too immersed in their individual realities to recognize the portions of others. Fatefully, the titular “wise old dwarf” appears and sends Dora and Pheldron to live together in an isolated cabin for four months.

Naturally, the odd couple begins their shared living arrangement with their fair share of difficulties and disagreements. Yet somehow, in the course of living side by side and sharing in the work of maintaining the cabin, the pair undergoes a transformation by means of challenging their previously limited worldviews. “They learned that there is more in life than Dora’s gladness or Pheldron’s despair.” Once connected, they taste a world beyond themselves. Without pithy “whataboutisms” or unfair comparisons, Dora and Pheldron grow not to discount their own experiences, but to expand their awareness to realize their interconnection.

The women painting the benches nearby pause their work: “That’s really a sophisticated message for someone so young to have written!” they remark in awe. They are, of course, correct. And Anne Frank’s legacy makes this children’s story all the more poignant in its emphatic insistence on our shared humanity, in its courageous embrace of human longing.

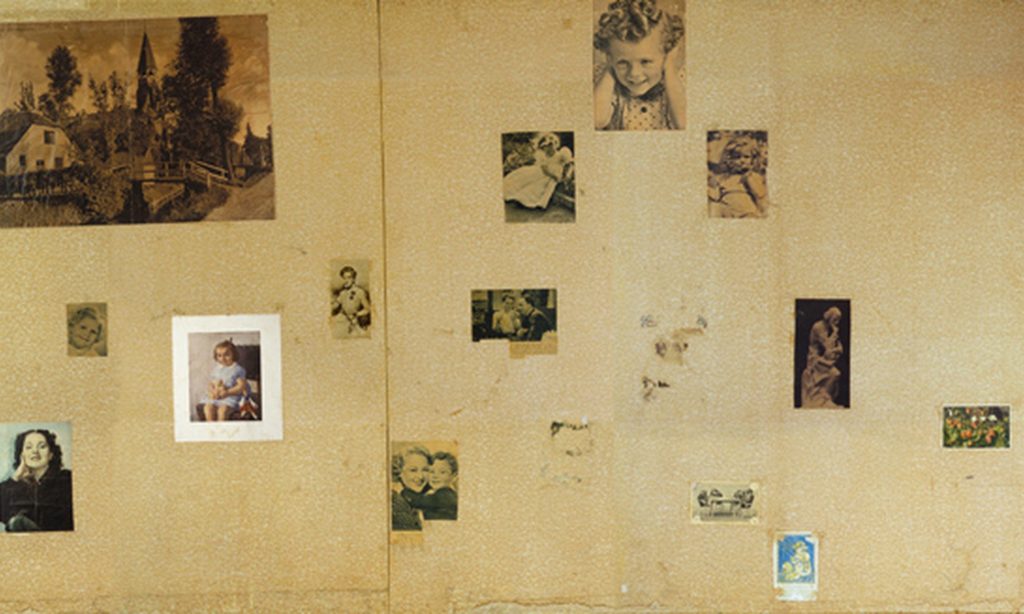

This past February, I was in Amsterdam. I toured Anne Frank’s house, and the moment that loosened my flow of tears was oddly mundane; there is a wall adorned with magazine clippings, postcard-sized images of movie stars and painted artwork, nature scenes and smiling young women showing off glamorous flared dresses.

‘Thanks to Father, who had brought my whole collection of picture postcards and movie stars here beforehand, I have been able to treat the walls with a pot of glue and a brush and so turn the entire room into one big picture.’

(Anne Frank, 11 July 1942)

Photo collection: Anne Frank Stichting, Amsterdam

It was so simple, so intuitive – we all love being surrounded by the basic elements that make us smile. There was so much essential humanity in that space; my tears mourned not a heroine but a girl who just wanted to live, live, live. My tears were for the fragile beauty of a girl who knew somehow the way to hold both pain and hope at once, to see beyond the narrow confines of the moment.

The siren feels like a minor blip just minutes later, and I almost question whether it was a figure of my imagination, whether my mind is getting loopy from dehydration. It was real, too real in fact. And meanwhile, I am here, holding the child.