“Like everything metaphysical, the harmony between thought and reality is to be found in the grammar of the language.”

~ Ludwig Wittgenstein

One of my favorite words to teach my students is juxtapose.

It is the voice of two. It says: Look. It says: Observe our contrast.

It is conceptual. It implies there is more to know. It says: Just suppose.

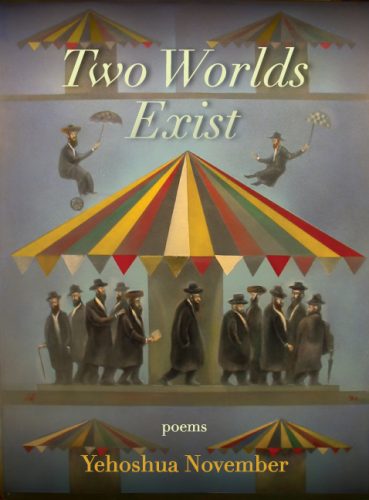

In Two Worlds Exist (Orison Books), Yehoshua November’s verses paint poignant narratives of life’s daily struggles given meaning through contemplative faith. Mundane, every day experiences are made profound with a humble, spiritual perspective of living with the certainty of uncertainty. By this same measure, tragedy—devastating and inevitable—is given significance and depth. Belief and practice do not make things easier because that’s not what they are meant to do. Chassidic teachings “do not erase [the] sorrows” of the believer, the poet tells us. Instead, we learn that we have a task, a struggle, and that “this is your life./ What will you do with it?”

In “Conjoined Twins,” November tells us the story of the springtime birth of two boys, would be brothers of his, who share a heart but do not survive. His father secretly arranges a circumcision, naming, and burial. In November’s care, this deeply felt narrative takes a turn when we find out their names, relating to the time of the year they are born, are Mordechai and Pesach, after Purim and Passover. Each name is then carefully, succinctly explained by way of the holidays with which they are associated. This allows the poem to end with deep import when “…[the Jews] left their bondage/ and arrived at the mountain/ where, the Midrash states,/ they camped in the desert/ like one man/ with one heart.” With these verses, November lifts the weight of the heartbreak into the light of a Torah concept and gently leaves us contemplating the spiritual possibilities.

It is moments like this that fill this volume.

Oftentimes November is more subtle, which is when he is most potent. In “The Bike,” the cousin who rides a bike to get out more after the death of his son is in the end shown to be “bent forward, peddling/ his son’s old bike/ into the long summer evening.” When bochurim are visiting a prison in “At the Request of the Organization for Jewish Prisoners,” the poet notices another visitor, a woman dressed revealingly who is told she has to change before entering the visiting room. The bochurim are there to share Chanukah with Jewish prisoners. They tell them “the story of the soul,/ which, against its will, descends/ into the body’s confinements.” As they leave the prison, the poet sees the woman they’d seen earlier and wonders at her earlier dress, imagines her preparing to visit her husband or boyfriend, and how she “must have inhaled deeply/ and then squeezed her body into the tight black dress.” It is impossible not to think of the earlier verses about the soul in comparison to these verses about the woman and her dress. This juxtaposition forces the reader to reconsider everything. “The Soul in a Body” takes this theme further and wholly imagines the soul as a Russian immigrant far from home. Even though “correspondence/ has been forwarded to this address,” the soul insists: “I am not from here. I am not/ from here at all.”

November’s poems, simply put, are beautiful in their provocation. Like the best poetry, they force us to look anew, to reconsider perspective, to reshape our own vision, if only for the brief time with these delicate verses.

His tone is contemplative and often rife with melancholy and nostalgia as he holds up every day, ordinary living—memories, tragedies, work hours, conversations with his wife—alongside the adherence to faith in a spiritual reality existing as a reflection of our own.

Rather than a strictly contrasting view, the juxtaposition these poems offer is one of a relationship. Yes, he says, there are two worlds. They are symbiotic. They are real. Our work, he shows us, is to be aware, to notice.

Cover image from Flickr.