This Sunday, November 30, Hevria writers Matthue Roth and Eric Kaplan will be having a book party for their new books! If you’re in New York, you should come.

Shlomo Carlebach said that gentiles tell stories to put themselves to sleep; Jews tell stories to wake themselves up.

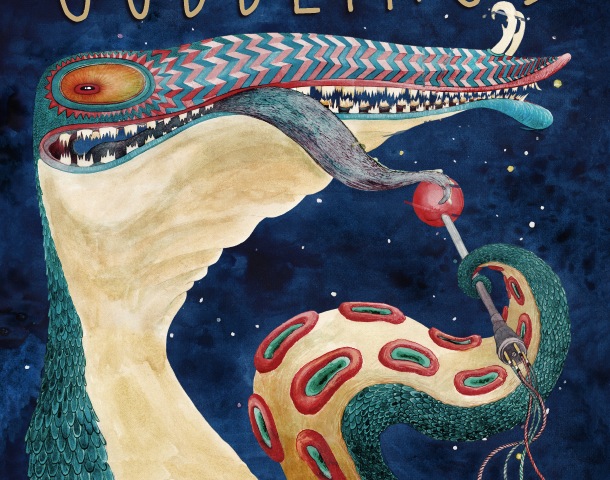

I wrote a picture book called The Gobblings that comes out this week. it’s about a boy named Herbie whose parents force him to move to a space station far away from his friends. A bunch of aliens are destroying the station, and only Herbie can save them.

Here’s a story: One night, I was stranded in a town called Frankston on the edge of Australia. We drove to see the fairy penguins swim in from the ocean with pre-chewed fish for their babies, then stayed for the night with my wife’s best friend and her husband. They had moved here fleeing from the crazily expensive Melbourne Jewish community, hoping that other families would follow. A year or so later, no one did. Their kids were lonely, and they were getting ready to move back. The next morning, all the kids were up, the adults were asleep, and they forced me to tell them a story.

That was where The Gobblings started.

Or was it?

Here’s another story, a story of the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidic Judaism. On Yom Kippur night, a boy wanders into a synagogue. He doesn’t know how to pray, he doesn’t know Hebrew; all he knows is the Hebrew alphabet. So he recites that and hopes the letters will rearrange into the right words. At the end of the story, they do, and his prayers not only bless him with a good year, but the prayers force open the gates of heaven and they save everyone else in the whole synagogue.

I loved that story, and it also freaked me out. Like, what was a boy doing wandering alone into synagogue? Why didn’t he just pray in whatever words he understood? But I also really understood it, because it felt like everybody’s experience praying. We’re all alone. We’re all shouting out to someone who might not be there. We don’t really know what to ask for — I mean, a nice house and money and lots of Legos would be cool, but we don’t know what we truly need.

I was not thinking of this Baal Shem Tov story on that way-too-early morning in Frankston. In fact, I wasn’t thinking much of anything. I’ve gotten good at the knee-jerk parent mornings — you hear the sound of kids about to kill each other, and you wake up. You do what you have to do. Eventually, you manage to scramble into normal clothes (preferably before your wife’s best friend comes down to find you in a t-shirt and boxers); you strap on your tefilin and your say the morning prayers. But until then, your only duty is to keep the peace among the kids.

In other words, my mind was not really thinking of much of anything.

Here’s another story. It’s a few months ago. My editor calls me. He’s somewhat frantic. “The sales reps aren’t sure how to sell this,” he says. “They know you’re Jewish. Does the book have anything to do with Jews?”

“Like, aside from being written by a Jewish kid?”

“Is there anything you can tell them? Anything that has to do with the book itself?”

“Can I get back to you?”

I feel a tinge of guilt. I’m not sure if I was thinking of that Baal Shem Tov story when I made up The Gobblings. Come to think of it, I’m not even sure if they hold up 1:1. Are the robot friends that Herbie builds himself the equivalent to our prayers? What does it mean when Herbie defeats the Gobblings — am I saying that praying to G-d is like fighting scary alien monsters?

“Sure,” says my editor. “Just let me know.”

I run away. I call my friend/mentor Laurel, the author of such picture books as (famously) Baxter, the Pig who Wanted to Be Kosher and (less famously, but completely awesomely) The Longest Night, what I should do. “I don’t even know if the story was in my head when I wrote it,” I confess.

What Laurel tells me is that we’re all the sum of our experiences — that every story we tell is a sequel to all the stories we’ve told so far in our lives. When the heroine of our last good-night story falls asleep, she dreams the next story we tell. And in that story, maybe the main character is the heroine of the last story, reimagining herself. To tell a story, she says, is a culmination of every story we’ve ever told in our lives, every story we’ve ever heard.

One more story. My oldest daughter, six years old and the wisest person I know, told me (quite instructively, but way too late for press time) that the story shouldn’t be called The Gobblings. It wasn’t about the Gobblings — it was about Herbie. “He saves the people from the gobblings,” she says. “So you should call the story ‘Herbie and the Gobblings’ or ‘Herbie Saves Everybody from the Gobblings inside the Spaceship’.”

(Which is a really good idea, and if you buy a copy from me, you can totally ask me to change the title page to say that.)

But what I said — and I promise you, I wasn’t thinking it until I said it — was, “How do you know this is Herbie’s story? Maybe he has another story.”

Her eyes lit up. And she told me Herbie’s story.

And maybe if I get a chance, I’ll tell you that one some day.

Shlomo was right — or half-right, anyway. Some stories put us to sleep. Great stories wake us up. But the best stories are the ones that wake us up and make us realize that our dreams weren’t only dreams after all.

Matthue and Eric Kaplan will be reading from their new books, The Gobblings and Does Santa Exist?, this Sunday at 2:00 P.M. at Mason and Mug in Brooklyn.