Fifty-two pages in, or a little less than halfway through his newest book, Sailor and Fiddler, which is not an autobiography — or at least, the author concedes, is “the closest to an autobiography I’m ever going to write” — Herman Wouk lets loose a plot twist in a most unexpected way:

[My wife] Sarah and I had encountered suburban Jewish eyebrows raised in amusement at learning we kept kosher. With New York’s Broadway and literary Jewish insiders we had clearly “made it,” but our ways disconcerted them as well. They saw us and socialized with us at Sardi’s, yet we declined their friendly dinner invitations. We were weird mavericks, no question. Christians like [screenwriter] Calder Willingham took us for granted; it was only Jews who found us odd.

Hold on a second.

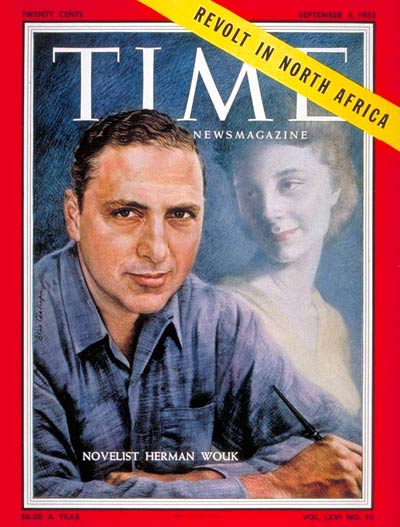

Let me tell you about Herman Wouk. Once upon a time, he was one of the most famous authors in the world. His book The Caine Mutiny, a military drama that was loosely based on his experience in the Navy during World War II, reigned the bestseller list for over a year.

His work was adapted into plays, films, Broadway musicals

You might have seen it in a used bookstore, one of the dustier ones that does more turnover in old paperbacks than the new, chick-lit bestsellers. Your grandparents probably owned a copy of War and Remembrance, at least — the serious-looking heavyweight book with the stark and serious cover whose spine was long enough for the title to be written across, not up and down.

The truth is, I never read any of those books. I first learned about Wouk in college, when I was first becoming Orthodox. He was an older guy who went to the same synagogue as me, the only Orthodox synagogue in Washington DC — I’d just started going there, since I’d just started being Orthodox. One day my friend Aaron said to me, “You see that guy? He writes books just like you, only he’s published,” and then, of course, I felt immediately threatened. A rival! I needed to check out his books. If he was Orthodox, there was no way he could be a good writer.

The shocking part was, I liked him. I liked him a lot. I grabbed the first books I could find, inadvertently bypassing The Caine Mutiny and the War books in favor, first, of a lightly comic farce called Don’t Stop the Carnival. It was about a New York businessman who buys a Caribbean hotel — a simple set-up, followed by hilarity ensuing, and a surprisingly compelling plot about cultural misunderstandings that somehow didn’t come off as racist at all, and a story full of tension and uneasiness where you were in love with every single character. (Little did I know at the time, or else my old-timey teenager self would have been absolutely repulsed, but Carnival was adapted into a big-budget Broadway musical, with accompanying album, by Jimmy Buffett.)

The book wasn’t about Jewish stuff, although the main characters were unquestionably Jewish. It seemed like every place they ate food in a non-kosher restaurant was deliberately choreographed, every time someone went for a swim on Saturday afternoon my alarm bells rang. It was nothing unusual for me and my newly-observant, newly-paranoid brain, but it was like, at the same time, I could feel Wouk’s brain being paranoid too as he choreographed these scenes. He broke the rules — well, his characters did, anyway — but he was being deliberate about it. He was no more violating Shabbos than a chess player loses a game because he offers up a pawn in service of a greater gambit.

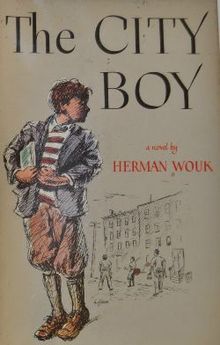

Next I read The City Boy, a coming-of-age story about New York before it got cleaned up. There too, I looked for traces of Judaism, and found Herbie eating corned beef from corner delis and sneaking into ten-cent movies on Saturday afternoon. The whole thing — especially for me, a who’d always been either rule-abiding or afraid to be a bad kid, read like an alternate history, a wish fulfillment of the bad kid I’d always wanted to be, running around the neighborhood and ruling it — and maybe, I thought, that was the way Wouk intended it.

I was becoming Orthodox, like I said, but still on very unstable ground. I was living on a couch in a house with two girls and a non-kosher kitchen, eating what I could. One of my roommates, a New England Methodist, came to me one night and confessed that she was dating one of my friends — one of my new friends, my Orthodox friends. “How do I learn about your religion?” she said.

I referred her to Wouk’s book This Is My God. It’s his Jewish anthem, originally an explanation of his beliefs to his non-Orthodox nephew upon his bar mitzvah, but expanded — and honestly, calling it that is belittling it beyond belief (pun intended). It’s a refined, clear, concise explanation of Torah Judaism, written for someone who’s never heard anything about Judaism, but explained so richly that anyone in the lifestyle would have no problem reading it; they might even, dare I suggest, enjoy it — it’s as close to a rational explanation of something fundamentally irrational as can exist, so clear and beautiful that it makes everything make sense. Punch line: the book lasted longer than the boyfriend.

Sailor and Fiddler, that non-autobiography I was telling you about, reads like liner notes, that part of the album that tells you about the inspiration of the songs and funny anecdotes from the recording studio. But honestly, all my favorite parts were the parts that talked about the books of his I hadn’t read. There was The Caine Mutiny, which sprung from his experiences fighting in WWII (linger on that for a moment: he was a Jewish soldier fighting Germany during the Holocaust); the War books; and Marjorie Morningstar, a five-hundred-plus page interior drama about a young woman who runs from New York society life to become a Hollywood actress.

The movie version of Marjorie starred Natalie Wood, fresh off her headlining performance in Rebel Without a Cause (she also played Maria in West Side Story). Marjorie was a cautionary tale in many ways, a girl who shunned her Jewish heritage, dabbled in miscegenation and, uh, immodest activities. Alana Newhouse, the editor of Tablet, makes a convincing argument for Marjorie‘s enduring popularity, despite the pragmatic conservatism of its underlying themes: “Like a literary golem,” she writes, “Marjorie seems to have upstaged her creator, seducing readers in a way Wouk likely never intended.”

But is that really upstaging Wouk? Isn’t the author’s goal to imagine the characters, to set events in motion and nudge the snowball down the hill, then stand back as it builds into an avalanche? In Sailor, Wouk comes off as a consummate entertainer: an artist, for sure, but more than anything a canny showman, someone who knows how to tell a story with just the right amount of adventure, humor and bawdiness to keep us coming back, and keep us wanting more.

I mean, for goodness’ sake, he was asked to write for Lyndon Johnson’s Presidential Inaugural Address. The story, in Sailor, is less than a paragraph long. But it’s crazy. And it’s good. He ate in John Lennon’s dining room after “promises of tuna salad on new plates,”* and then he skips right to moving out of NYC to Washington. This is a guy who’s spent more time writing stories than most of us have living them. He knows how to make each word count.

And he did. Wouk is far too much of a gentleman to address this in his writings, but his own skirting between Jewish law and writing and society life has got to be riveting. Like Norman in Carnival, he bought a lavish house in the Caribbean, and moved there for 5 years with his young sons; and I, with young kids of my own, buried in New York and wishing for a way out, have to ask, how the hell did he pull it off? The food? The schooling? The chutzpah?

And yet it’s awesome how different all these books are. Marjorie is about New York and L.A. society; Youngblood Hawke is a riff on down-home Southern wisdom; Inside, Outside is about a Russian-Jewish

Wouk published Sailor and Fiddler on the occasion of his 100th birthday, vowing that it would be his final book and that now, ensconced comfortably in the California desert, he will put the pen down and get some rest. That might make life a little less joyous for the rest of us.

But not really. For those of you like me, who are late to the party, there’s an entire career to catch up on. And for those of us who are juggling with the dilemma of our belief and our storytelling ability, how they fit together and whether they fit together at all, well, don’t stop juggling. Here’s a guy who made a whole career out of figuring it out.

____

* — That’s a paraphrase; the book’s stuck in a room with my sleeping newborn. Sorry, journalistic integrity.