I started working out because I am cheap. There a zillion amazing things about working for Google, including free lunch (yes they order in kosher stuff for me) (but from a steakhouse, and I’m a vegetarian, so I eat a lot of pasta), but because I am a contractor — yes, even though I’ve worked here for 2 years — I don’t get basic things like healthcare.

So I feel this need to take advantage of every little bit of free stuff that does come my way.

At least, that’s what I told myself when I started. I really wasn’t prepared for this.

I wasn’t ready for working out to run my life.

*

On the TV show Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the vampire Angel was given back his soul, then cursed by gypsies that he would lose it if he ever found true happiness. In Buffy canon, “true happiness” meant having sex, but for me, these days, true happiness mostly happens in two instances: when I am playing with my baby, and when I am working out.

With my baby, I know happiness is fleeting. She goes from laughing to tantrum in zero seconds flat. I know how temporary her laughter is, and how fleeting: that’s why I hold onto it every chance I get, why I treasure every giggle bestowed upon me and every fleeting smile. I’m not thinking about whether or not my contract will get renewed at work. I’m not worrying about bills, or grades, or whether my sweater is dirty or where else I’m supposed to be. In that moment, all that really matters is that my daughter is laughing, and that’s all that fills my head.

Working out is different.

*

There’s a mindlessness that comes from working out that gives you a sense of zen. The repetition of lifting a weight, no matter how heavy it is, gives you both a sense of purpose and a sense of openness. My arm goes up, my arm goes down. The weight goes up, the weight goes down. I’m staring across the street at a Manhattan-white building — that means it’s a dirty gray, the color of marble in a museum — and a zigzagging staircase that runs across it, painted bright blue. I stare at that for a while. The zigzag imprints in my mind. I’m thinking about nothing but the staircase, letting my body do its thing, and then I’m thinking beyond the staircase, about the building, the city, the universe.

It is, bizarrely, mindful.

*

I haven’t gone to gym class since 9th grade. Ms. Doyle, who ran the school’s sex ed clinic, struck a deal to give me gym credit if I volunteered for a couple hours a week, keeping the brochures in line and handing out condoms to kids whose parents had filled out the appropriate paperwork. (I myself had no need for condoms, although I often carried one around “for friends” — I didn’t have a girlfriend, and I was light years from being sexually active, but I treasured the idea that I theoretically could be, that my body was filled with that potential, and that people all around me might be engaging in sex at this very moment, and that I could assist them in their endeavors.)

I was a nerd. I had as much need for gym class as I did for condoms. I resented my body on a daily basis. I wanted to know as much as my brain could fit. I wanted to scorn my body, as unattractive to me as it was to any girls I could possibly like.

More than that, I didn’t want to understand my body. It seemed like such a waste of time. Thoughts and emotions were so much more complicated, and they were what ran my relationships. Maybe I should just focus on those instead, leave my body to the wayside.

*

My Israeli neighbors’ kid is a personal trainer. Way before I ever thought I’d be caught dead in a gym (or, more unlikely, alive and kicking), I sent him a text message on a whim: I want to start lifting weights in one hand while I’m reading a book in the other. What weight should I start on?

He never answered. I think he thought I was kidding.

*

In truth, I’m so glad he never replied to me. I just bought a 15-pound weight and started doing it, but not seriously. I could work out on my own (and now, nearly a year into it, I sometimes do), but it helps to be in a class — to have a trainer there, calling out exercises for you to do, giving me an assignment and then making me complete it.

A friend told me that he could never work out. “It’s so boring,” he complained. But I think that’s the point. You’re paying attention to stuff you never thought to pay attention to. You’re being mindful and grateful of absolutely everything.

I wish I could go back in time and tell my 9th-grade nerd self: it’s more like homework than you dreamed it could ever be.

*

It’s good to have something I’m not good at. That sounds like a brag, but it isn’t. Most things in this world, I don’t know how to do at all: flying an airplane. Folding shirts (I mean, I do it, but apparently I’m not very good at the right way to fold shirts). Braiding my daughters’ hair. There are a few things I do that I’m very good at: English grammar. Dad jokes. Getting the Google Assistant to tell you dad jokes.

But working out is something I’m not amazing at. I also don’t need to be amazing at it. It’s a skill that I’m okay at, that I’m getting better at, little by little — for three-point lifts, I started at fifteen pounds. After a few months, I increased to 20. I don’t remember the point where I switched to 25, which in itself feels like an achievement, and now on a good day I can do 30.

But the point is, I don’t need to do it. Even better: I can be a crappy weightlifter, and it’s okay. The measures of the weights I lift are like a video game. While you are doing it, it means everything to you, and the moment you step away, like your highest score ever in Donkey Kong or that ultra hard radiation dump of Half-Life that you made it through, once you walk away it evaporates.

*

From New X-Men #131, written by Grant Morrison, penciled by John Paul Leon:

BEAK: I don’t drink or do drugs. I’m hardcore straightedge. My body is a temple.

ANGEL: Yeah, a temple to Satan, you weirdo. You look like a freak.

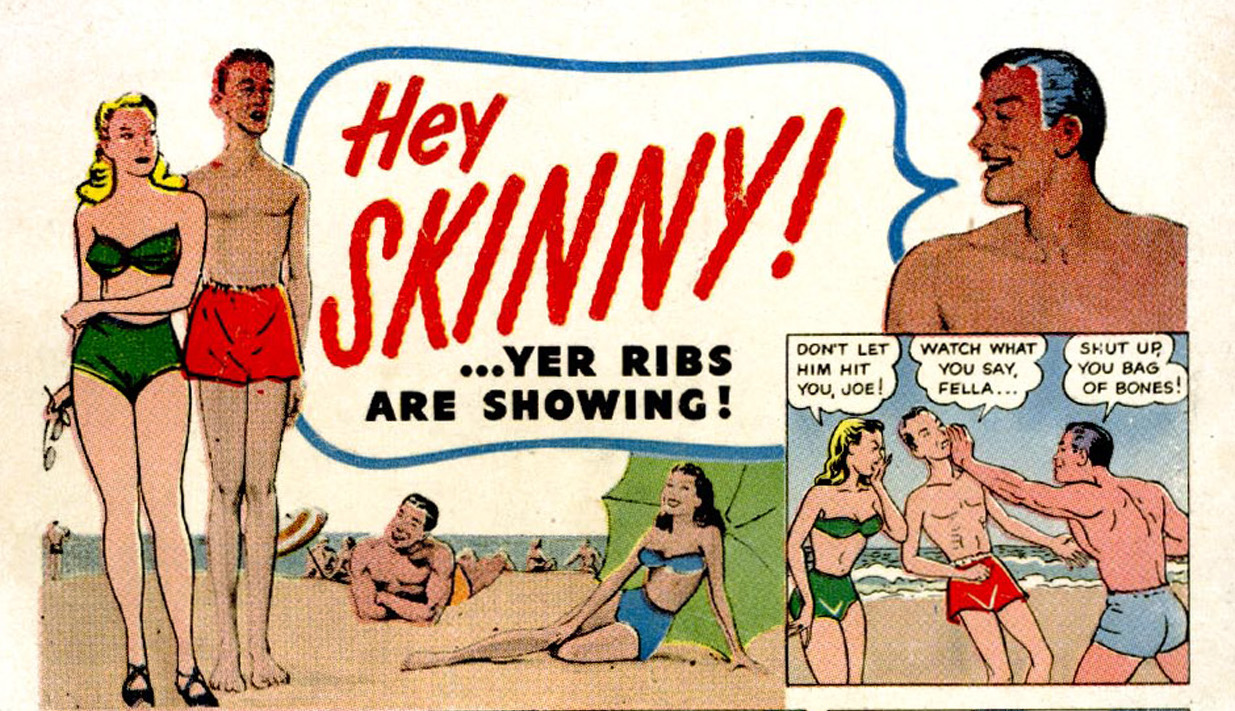

I kind of feel that way. I used to be skinny. Then I became skinny with a potbelly. (Body image: basically this.)

And I know that G-d gave me my body, and I am as grateful for it as I am for being alive — the first prayers we say in the morning are thanking G-d for giving us our bodies, interspersed with a prayer thanking G-d for giving us our Torah and our minds and our stories. And while I can totally understand that, understanding my body has been harder.

*

Working out isn’t mindless at all, it turns out. You need to concentrate. You need to have in mind every body part at once as it moves. Once I’ve got my knees in position, my feet are pointing different ways. When they’re all aligned, my back is curled. I fix my back and my shoulders are ajar. And all this time my head is lolling to one side, gazing out past the staircase, where between buildings I’ve found a narrow slice between buildings so I can see to the water.

Focus.

Bring yourself back.

*

Lately I have been afraid of losing my body. Not that I’ve ever had much of one. But I had a lot more trouble keeping up with my second baby than my first baby, and the third kid was a lot heavier than the second. I didn’t want to turn into one of those people who has to grunt and gruffle as he stoops to pick up his kids’ toys.

I have no illusions that my body’s going to last forever. I have no illusions that it’s doing that well now. But the world is recreated from nothingness at every moment, and that means we have every moment to restart our lives. So here’s me restarting mine in this direction.