“God forbid.”

This is a phrase we use when we are afraid of something happening, something tragic and permanent. Genocide, the death of someone young, natural disasters, and disease.

Also, apparently, it’s the word a lot of people use when someone stops believing in Judaism.

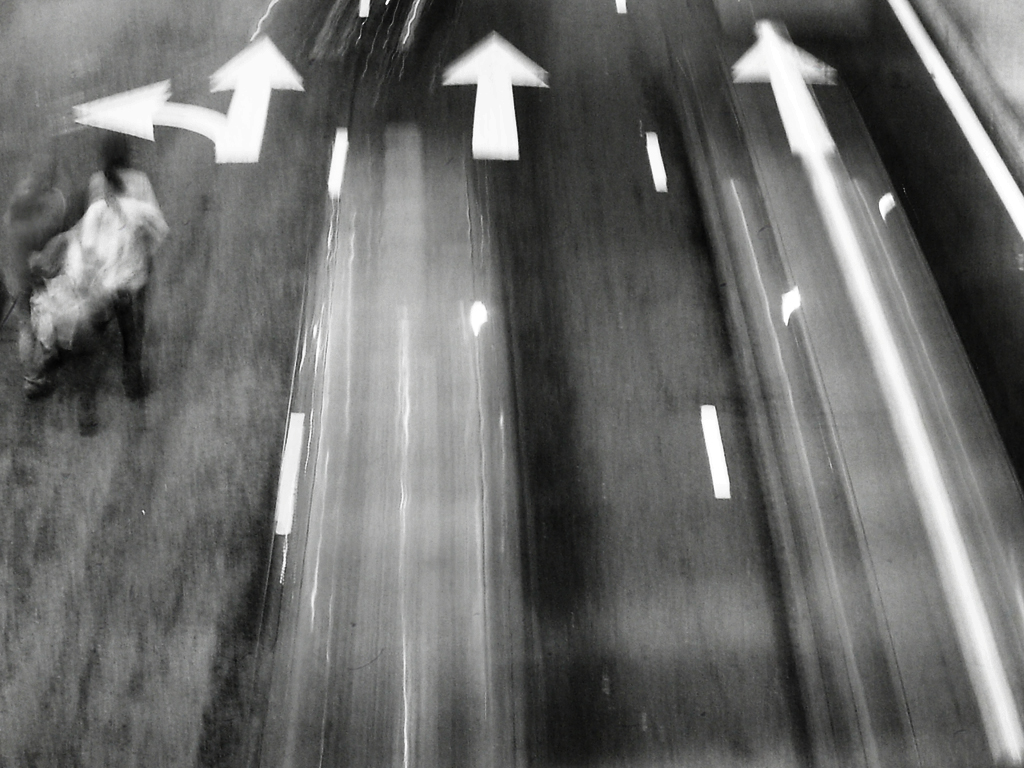

I suppose that’s why they call it “off the derech”. It’s a tragedy that we must do everything we can to avert.

Today, we look at polls, and we see a vast number of unaffiliated Jews, growing every moment. Those in the orthodox community see so many of their people leaving that some of them even see it as a crisis. Google “off the derech” and you’ll see many hand-wringing pieces about the “why” of going off, of people choosing to no longer believe, to no longer love Judaism and its beliefs or even to believe in God at all.

And so, this fear, this hand-wringing, drives so many in the orthodox world because they see losing belief as a permanent state that someone enters into, a danger, an endless pit where our children will be lost for all time.

It’s no wonder, then, that the orthodox community also approaches kiruv in the same way: they assume that once a person becomes religious that the job ends there. After some digging, I’ve discovered that some of the biggest donors to kiruv organizations actually base the amount of money they give (or whether they give at all) to these organizations is based off the “conversion rate” that this organization achieves (ie how many people they turn orthodox).

“God forbid.” “Please God.” Two sides of the same coin: seeing reality as fixed, as permanent, choices as set in stone.

Also, both statements that in this context violate the commandment to not use God’s name in vain (maybe not officially, I’m no rav, but in spirit).

There have been studies recently about the effectiveness of “fixed” vs. “growth” mindsets.

In America, and in most of the West, we tend to think with fixed mindsets. Fixed meaning that we see things in black or white, permanent, unchangeable terms.

Thus our literal idolization of celebrities, who we see as possessors of some sort of special, magical powers that if we could only touch we’d be blessed. Thus our obsession with grading in schools, standardized tests, elitism, etc etc. The way people either love or loathe politicians like Obama. Our deep need for heroes.

Every single one of these ways of looking at the world comes from a perception that the world, and people, are “fixed” in some way. They were born great. They were born evil. They were born heroic. And nothing will ever change that, except a miracle or a catastrophe.

This is the way much of the hand-wringers and the big donors of kiruv and so many others in the orthodox world look at the world. They use the words “God forbid” when talking about a person leaving Judaism because they see the decision as permanent, as unchanging. This is why you will often hear the argument pushed by orthodox rabbis that the primary reason people go “off the derech” is that the person was mentally ill. There must be something defective with the person if they choose to stop believing in Judaism (orthodox Judaism at the very least, let alone Judaism altogether).

There’s no way that choosing to leave could have been a rational decision. Or a virtuous one (imagine!). No, there must be something deeply wrong with the people who leave Judaism, inherently, deep within them, that can only be fixed with medication or therapy or drastic kiruv intervention.

Even worse, and this is the true tragedy, people approach their own Judaism in this way. They limit themselves, their thinking, and their perceptions of reality based on the fear that they will leave the road of Judaism and travel onto the dangerous, no-holds-barred secular world.

And so they don’t challenge themselves or their own beliefs. They perhaps challenge themselves within the framework of Judaism, but they do not challenge themselves as souls within fallible bodies, as limited minds in an unlimited, vast world.

These people live lives of fear, even if they don’t realize it, even if they don’t accept it, even if they’ll never admit it. To them, they are either on or off Judaism, and they live with the constant fear that if they question anything about their beliefs or, in more extreme cases, their leaders, that it is a sign that they are off, and that would be the absolute worst thing because then they’ll be one of those people who are defective and unworthy, the very same people they most likely attack and deride.

To be clear, this perspective has nothing to do with being Jewish, it has to do with having a fixed perspective of the world, of ourselves, and of others. It applies, as I pointed out, just as much to the secular world as it does to the religious one. The difference being that in the secular world, the spiritual belief system is so loose that this aspect of being on or off is not nearly as powerful as it is in the religious world when it comes to religious belief.

Then there’s the growth perspective. As has been proved in many studies, having a perspective of growth as opposed to fixed, on average, causes us to be happier, more successful, and more fulfilled.

A growth perspective sees a person not as a product, not as an end result, but as a process. An ever-changing ecosystem of inner reality.

Thus, someone who does bad in school doesn’t see themselves as a failure and works to get better at what they do. Parents don’t see their kids as off for “failing” at school either because they believe their children can always change, always evolve, always grow.

It is for this reason that parents these days are encouraged to praise their children for working hard rather than for being “smart”. When someone tells their children that they are smart, the children internalize that their worth is based on something fixed, and if something happens to disprove this reality of “smartness”, then they fall apart because they think that they actually aren’t “smart”. And so they spend their lives simply trying to prove to everyone around them that they are smart, and any growth or change or hard work is thus motivated by this fear of not being smart.

A child who is praised for working hard, however, sees life differently. If he fails, he tries harder. He does not see his worth as determined by his performance. Rather, he sees himself as possessing an inner worth that cannot be changed. What changes, what grows and evolves, is his approach to life. He sees himself, then, as a process and not a product.

It’s time for the orthodox world (and, of course, the world at large) to start seeing life from a “growth” perspective. It’s time that we stopped saying “God forbid” about someone deciding to stop believing and “Please God” out a hope that this person will begin to believe.

Every time we do this, every time we look at going “off the derech” (and every time we use that phrase), we are projecting a fixed reality onto the person we are discussing, whether it is someone else or ourselves.

Belief is not a fixed reality within us, rather it is something that must be constantly grappled with, constantly attacked from different angles, constantly reevaluated.

Is it any wonder that one of our most foundational texts, the Talmud, is so full of arguments, of debate, of unsuredness? No text further pushes us to be uncertain about our own certainty, to more adopt a “growth” perspective when approaching our spiritual beliefs than this text that practically every orthodox Jew learns.

I can say with the most confidence I’ve ever had when discussing the orthodox community’s “issues”, that the vast majority of the problems in our community, no matter whether Hasidic or modern, come from a “fixed” perspective on the world.

For example, that we see a Jew who wears a more “pious” garb as actually being more religious than us. The shidduch crisis, in which men and women choose (or don’t choose) their potential spouse without taking into account that this is a person who will change and evolve with them once married. The attempt to defend all people of authority, even of the most heinous charges, because people would rather believe that the accusers are evil than the accused, since one of those two already holds the “fixed” position of hero or sage or perfect.

The inner battles, also, so often, stem from this place. This compulsive, obsessive need to stay “within the lines” and to never look outside them. The inability to accept that our beliefs can evolve. An inability to trust our inner voice. Choosing not to pursue passions such as as creativity/art because we believe that those are “slippery slopes” (another fixed-view of the world).

When we come from a growth perspective, suddenly our view of ourselves and our fellow Jews completely shifts.

For example: no longer is a person in a black suit and hat considered to automatically be more religious than a Jew without one. Marriage material isn’t based on whether the person’s resume has a bunch of checkmarks filled out by it, but based on whether we see this as a person we could grow together with. Authority is suddenly not quite as authoritative (a scary thought for many), because there’s a potential that it may slip, or may not be quite as “fixed” in place as we thought it was. And all of that is okay, because that’s how the world works! Change is the constant, process is the reality, potential falseness the truth.

And what’s not okay now? The Jew in the black garb (or any other Jew, of course) who does not live the life he wants to live, or who is not using as much time as he can to be spiritually engaged with God and his soul. A marriage based on a name or money or looks. Authority accepted simply because it is authority.

The way we view our own approach to belief changes as well. Suddenly, we can explore the world with open eyes. We can question ourselves. Our inner spark is now a flame, alive and unafraid to venture into the darkest of territories, because what matters to us is discovering how we can further ourselves, discover deeper truths, and evolve to our best selves. We no longer need to prove, like the “smart student”, to others or to ourselves that we are worthy, that we are believers, that we are on.

And thus we return to the matter of “God forbid” and “Please God.” Of the “off the derech” and “kiruv” phenomenons.

Imagine, for a moment, that you see the world as a world of growth, and people as creatures of growth (or maybe, hopefully, you already do). Suddenly, a person leaving Judaism is not the end of the world. Why? For many reasons. First of all, a person who has made this choice, at the danger of being ostracized by their community and disappointing their parents and family, has done something brave (whether we agree with the choice or not). They are, most likely, people who are deeply engaging with their spirituality in some way.

Of course, there may be other reasons, but the point here is that now a whole new world opens up when we see such a person make a choice that others deem tragic. It is now simply another chapter in the story of their life.

There is nothing defective about such people, nothing wrong with them, nothing we should be afraid of. They are Jews, and always will be, but they are Jews who have chosen to follow a different set of beliefs. It is not the end of the world, it is, in fact, quite the opposite. It is the beginning of a new life of spiritual engagement in their lives, and an opportunity for any Jew with a growth perspective to engage with them as equals rather than either spite them as evil or bribe them to come back.

Which brings me to kiruv. Imagine again that you see the world from a growth perspective. A person becoming religious means very little in the short term. It simply means that, just like the person who has chosen to stop believing, this person has opened a new chapter in the book of their life.

Now, someone from a fixed perspective tends to see their work as over when this occurs. But someone with a growth perspective understands this moment for what it is: an incredibly delicate, incredibly powerful, moment in which this “religious” person now needs constant encouragement, love, and guidance.

There’s no way to measure success in this reality, at least not in the short term. “Conversions” mean nothing because life isn’t a financial transaction, where one thing is exchanged for another in a structure of permanent change. Rather, life is growth. And what matters, then, to a newly religious Jew, is not that he has made this initial choice but how he approaches his Judaism and his spirituality and his relationship with God.

In other words, the how matters more than the what. The process matters more than the product.

Unfortunately, we still live in a world of fear. A world of “fixed” mindsets. And so this utopian vision of looking at life as an evolution, a changing reality, simply doesn’t exist. It is changing, because life is on a constant path towards Moshiach, thank God, but it’s time we started approaching this split of perspectives head-on.

Imagine a world where science and religion aren’t enemies but friends because we have already internalized the reality that spirituality within and without is in constant flux. Imagine a world where every Jew is valued and considered a part of our community (even if they don’t consider themselves as such) because we no longer measure them based on whether they are broken or perfect. Imagine a world where you aren’t valued as a product coming out of a factory, but as a beautiful piece of art that is constantly being created, constantly being painted and written and played. And you and God are the artists.

This is not a world, in fact, that needs to be imagined. In fact, it is the world of “fixedness” that is imagined. Instead this world of growth simply needs to be revealed as the way the world already is. It simply needs to be shown, and we simply need to learn the tools to approach it in that way.

That’s all.

Everything else is commentary.